Domesday Book

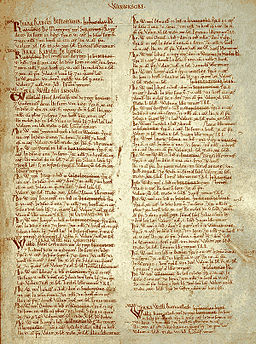

The Domesday Book, our earliest public record, is a unique survey of the value and ownership of lands and resources in late 11th century England. The record was compiled in 1086-1087, a mere twenty years after the Norman Conquest, at the order of William the Conqueror.[5]

"Its name 'Domesday', the book of the day of judgment, attests the awe with which the work has always been regarded. The earliest names accorded to it 'the King's book' and 'the great book of Winchester', where it was first kept, in the royal treasury, were displaced as early as the twelfth century by a title which recalled the wonder with which the subjugated English had seen their Norman lords called to deferential account." [1]

William commissioned the survey on Christmas Day in 1085. Ironically, it was the only census of England before 1801.

Topics |

William the Conqueror

William commissioned the book because his power was being threatened from a number of quarters, the rebellious North, Denmark, and Norway, during the last years of his reign. However, the book was more than just a fiscal record. It provided a detailed record of all lands held by the king and his tenants and of the resources that went with those lands. It recorded which manors rightfully belonged to which estates, and was also a feudal statement. It revealed the identities of the landholders, who held their lands directly from the Crown, and of their tenants and under tenants.

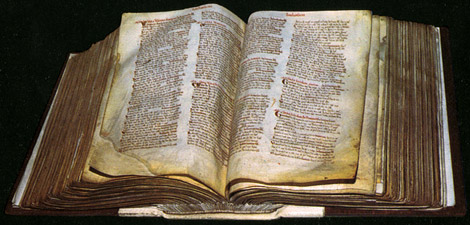

The inventory, written in Latin, contains a wealth of information that illuminates one of the most crucial times in history - the Conquest and settlement of England by the Normans. The original book itself still survives, preserved for centuries at Winchester, the capital of the ancient Saxon Kingdom of Wessex, and is now held in London at the Public Records office.

The name "Domesday" refers to the book of the Day of Judgment and as such refers to the reverence the book has always held. But before the name Domesday, the book was called the King's Book and the Great Book of Winchester. The latter reference was coined because of the aforementioned location at Winchester.

Great and Little Domesday Book

The text consists of two volumes: Great Domesday, which is now bound in two parts, and the Little Domesday, which is now bound in three parts. The Great Domesday describes 31 counties while the Little Domesday covers only Essex, Norfolk and Suffolk. The names refer only to the size of the volumes, not their importance. Ironically, the Little Domesday is of greater bulk than the Great Domesday because less abbreviations were used and it contains greater information for many of the entries. It is important to note that the Books are not censuses because they record only the head of households.

Like censuses of today, it was out of date before it was completed. Estates changed hands during the survey, and of course livestock, which were dutifully listed in many places, expectedly changed.

The English Translation

The text was written in an abbreviated and stylized clerical Latin that would make even the experienced Latin scholar cringe at the task of translation. The first translations appeared in the 19th century and it was typically a task done by county historians. The quality varied greatly and as such, in the 1960's Domesday scholars agreed that a uniform translation would be in order. Dr. John Morris (1913-1977) of University College, London assembled and led the team of Medieval Latinists in 1969. By 1975, the first county volumes were in print. Unfortunately, Dr. Morris did not live long enough to see the completion of the 35 volume set published by Phillimore & Co. Ltd, Shopwyke Hall, Chichester, West Sussex, PO20 6BQ, England.

Domesday Example Entry

Original:

De Williamo tenet Ricoardus iiii hidis in BERMINGEHA. Terra

est vi carucis. In dominio est una./ v. villiani / iiii. bordarii cum .ii. carucis

Silva dimidia leuga longditudina. / ii quarentine latitudine. Valuit / valet xx. solidos

Vluuin libere tenuit Tempore Regis Edwardi.

Translation:

From William, Richard holds four hides in Birmingham. There is land for six ploughs, in the demesne, one. There are five villagers and four smallholders with two ploughs. The woodland is half a league long and two furlongs wide. The value was and is twenty shillings. Wulfwin held it freely in the time of King Edward. [3]

Use of Forenames

It is important to note that there are scattered references to first and last names that were obviously in use at that time throughout the reference. For example, names like Gilbert Tison, Ralph Paynel and Robert Malet were found in Yorkshire. Trade names like Walter the deacon and Walter the crossbowman were already very much in use. Norman influence in names like William de EU and Roger de Lacy are very common.

Terms used in the Domesday Book

There are three terms found in the Domesday Book which were used to express the amount of land held by each manor, and how well that land was utilized, so as to estimate the annual rates of taxation upon each lord.

These terms are CARUCATES, BOVATES, and PLOUGH. The carucate was equivalent to approximately 120 acres, the bovate represented about 15 acres, and the plough was reckoned to be sufficient for half a carucate of land, or 60 acres. So, if a lord held vast lands, say two carucates, or approximately 240 acres, but only three ploughs, then at any given time one quarter of his land would lie fallow, and could not be worked. Therefore, taxing him on the assumption that all of his arable land was actually producing income would be unfair. On the other hand, taxing a lord strictly on the basis of how many ploughs he had would also be unfair because there was always the possibility that a lord with extra land might lease some to a neighbor who had more ploughs than land available for those ploughs to work.

By recording the amount of land available and the tools with which it was worked, it became a simple matter for a tax collector to visit once a year and estimate how well the lord had done that year and set the taxation rate accordingly.

HUNDRED derived from the Danish or Norse word wapentake which literally meant the taking up of weapons that were laid aside after an agreement was first used by the Saxons between 613 and 1017. One hundred held enough land to sustain approximately 100 households, or in other words land covered by one hundred "hides".

While this term was not Norman in origin, the Normans were quick to replicate the Saxon term and use it in the Domesday Book. Many of the original hundred names have been given to modern government districts. The term survives today in England, Wales, South Australia and parts of the United States where counties in Delaware, New Jersey and Pennsylvania were divided into hundreds in the 17th century.

SHERIFF derived from the Old English word scir-gerefa, was the royal officer in charge of a shire and responsible for judicial and financial functions that included overseeing the royal estates and custody of royal castles.

TENANTS a term derived from the Latin tenere which means to hold, denotes a person who held a property but did not retain ownership. This feudal term dates back to before the Domesday Book when land was never privately owned but leased. Undertenants were people who sub-letted part of the tenant's land.

TRE was used frequently through the reference. Derived from the Latin "Tempore Regis Edwardi," it literally meant that the land was held "in the time of King Edward I," or in other words before the Conquest in 1066.

VILLAN derived from the Latin word villanus meant villager, the same as the Old English term tunsman. They held a higher position than a BORDER who was a peasant.

Domesday Book Today

Like any other census, the Domesday Book was out of date by the time it was complete. Some estates had changed hands and tenants had died or moved. Today, the reference is like no other; it captures the life and times of an early Britain, right down to the number of livestock held in a a specific area. Most properties are valued in either pounds or shillings.

Copies in modern text have recently been republished, and provide an excellent insight into the types of surnames in use at that time. Check your local library or book store for a copy.

See Also

References

- ^ Domesday Book, A Complete Translation. Editor: Dr. Ann Williams. Penguin Books, 1992.

- ^ "File:William the Conqueror - c. 1580.jpg." Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. 14 Oct 2017, 11:39 UTC. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:William_the_Conqueror_-_c._1580.jpg&oldid=262845293

- ^ “Birmingham in the Domesday Book.” Citizenship, The National Archives, http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/citizenship/citizen_subject/docs/domesday_extract.htm

- ^“Discover Domesday.” Domesday Book, The National Archives, 26 Apr. 2017, http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/domesday/discover-domesday/

- ^"The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle". Translated by Giles, J. A.; Ingram, J. Project Gutenberg. 1996.

- ^ The Domesday Book, England's Heritage Then and Now. Editor: Thomas Hinde. Colour Library Books, 1995.

- ^ Swyrich, Archive materials